“There is no subtler, nor surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction and does it in a manner which not one man in a million can diagnose”

John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946)

Let us now unravel Keynes`s quotation

Definition

Inflation is a rise in the AVERAGE level of prices.

The most precise measure of inflation would include a record of all price changes for all products over a given period of time using one designated currency.

As this is not practical inflation is usually measured by government using carefully selected, necessary and important products that are available to view in a basket: 80.000 in the US and 743 in the UK. These products are weighted to reflect the proportion of income spent on each of these items.

Over the years and in different places this definition has been slightly changed often adding ambiguity. Some economists just refer to a rise in prices while others say a rise in the general level of prices. To avoid any ambiguities it is important that we always refer to inflation as a change in the average.

A brief history

Throughout this article it is the UK that will be the background for evidence, but the explanation applies to all countries with their own currency and Central Bank.

In 1923 John Maynard Keynes had published “A Tract on Monetary Reform”. In this he used the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) to identify the cause of inflation. In its simplest form it was an equation (some prefer the description as an identity) with a monetary side and a real side. Given that all its measures are related to a defined time period the monetary side included two variables. One is the stock of money (M) and the other is a flow of money which is a measure of the speed a certain quantity flows through the economy over a given period of time. This velocity is given the symbol (V). Together the stock and flow of money MxV identify the level of monetary demand used in exchange over a given period of time. On the real side of the equation there are the transactions that took place (T) and the prices paid in exchange (P). The result is the equation/identity MxV = PxT, which is referred to as the Fisher equation after the economist Irving Fisher (1867-1947). During the period of measurement any or all of these variables can change independently in either direction. Given the Quantity Theory of Money Keynes identified the cause of inflation as an increase or excess of monetary demand (MxV) such that the same number of transactions must have been exchanged at a higher average level of prices.

In 1936 Keynes book “The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money was published. In this book money was given a more subordinate role and the monetary side of the economy was referred to as aggregate demand and the real side as aggregate supply. A new concept was introduced which was a full employment equilibrium and when the economy was under full employment then aggregate demand was less than that required to achieve full employment and when over full employment occurred then inflation would result from excessive aggregate demand.

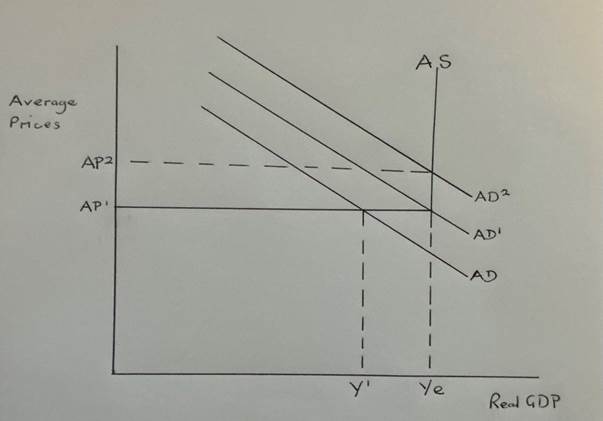

Keynes died in 1946 and his followers, the Keynesians, used his General Theory to advise government on how they could achieve full employment and manipulate aggregate demand to achieve it. Keynesians used a diagram as seen below to explain how their demand manipulation would work. They often used two versions of the aggregate supply curve. This one is perfectly elastic up to full employment and therefore no inflation will occur before full employment is reached. Alternatively there was a version that included an upward sloping aggregate supply curve that would trade off more employment and more inflation up to full employment,

In the diagram Ye is represented by full employment and Y1 is the current equilibrium. The Keynesian solution was then to shift AD outwards through the government running a budget deficit until they achieve an equilibrium at full employment. (Ye). Should aggregate demand be higher than AD1 as illustrated by AD2 then over full employment would result in a rise in the average level of prices from AP1 to AP2 and a budget surplus would be required to dampen down the excess demand. If all the numbers were correct then all the government had to do was act as a thermostat and maintain the economy at full employment and not let it get too hot or too cold.

At this point there was a potential problem if the theoretical full employment equilibrium was incorrect and was actually at Y1 or any point to the left of Ye. This would mean that every attempt to get from Y1 to Ye would be thwarted by inflation. This problem was solved by the Keynesians who introduced another possible cause of inflation which could raise the average level of prices at less than full employment and this led to the introduction and acceptance of cost push inflation. Now inflation could be caused by a rise in wages, oil prices, energy prices, food prices, property prices, greedy businesses raising their profit margins etc. Seemingly the problem is now solved for the Keynesians as inflation that occurs below the prescribed level of full employment can be identified as cost push inflation and inflation that occurred at full employment was demand pull inflation.

There is an important error in this thinking that we will expose towards the end of this paper but before that we will look at why it was so easy to accept cost push as a cause of inflation. Firstly the Keynesian experts did not want their full employment target questioned and government always preferred to be advised that they could continue to budget for a deficit as there were few votes in surplus budgeting.

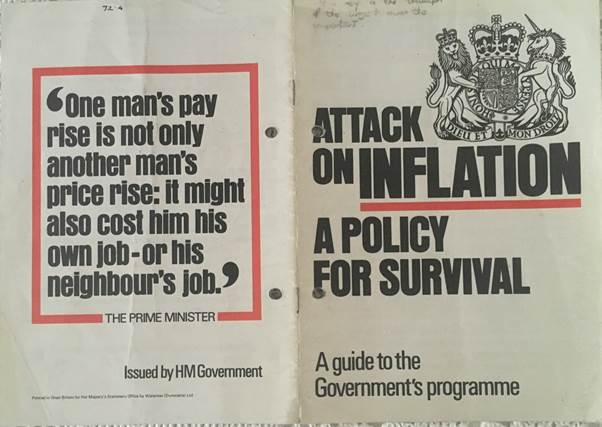

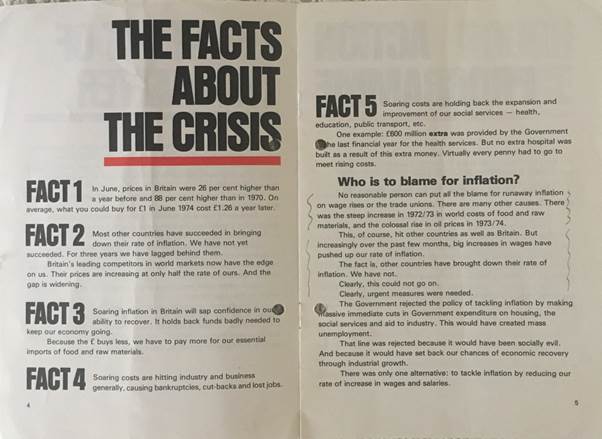

During the decade of the 1970`s in the UK successive governments were happy to be told to continue budgeting for a deficit even though inflation rose as high as 26% per annum and unemployment was not falling back to the full employment target. At the time Harold Wilson, the UK Prime Minister, argued that all inflations were cost push caused by excessive wage increases and the quadrupling of oil prices as illustrated by a government issue that went out to every UK household.

In an attempt to stop this cost push inflation the government of the day introduced a Prices and Income Policy to hold down prices and wages. Needless to say it was unsuccessful as the Central Bank was still expanding monetary demand faster than any growth in capacity in the economy.

The idea that cost push inflation is still the cornerstone of inflation is brought right up to date by Modern Monetary Theory which also claims that almost all inflations over the last 100 years are cost push inflations. From this they argue that there is always scope to increase government spending as long as there is no demand pull inflation and there is an output gap to close in the economy. It is clear that Keynesian economics and Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) are populist and exactly what politicians want to hear. They certainly did not want to hear from Keynes.

“By a continuing process of inflation governments can confiscate secretly an unobserved an important part of the wealth of their citizens”

The theory and the reality

Let us now logically dissect what inflation is and whether it can be caused by cost push and demand pull factors. As inflation is defined as a rise in the average level of prices it must be measured as more units of money used in the same number of transactions over a given period of time. From the demand side of the economy there are only two ways this can happen and that is if the stock of money is in excess of the economy`s output or the same stock has circulated more quickly through the economy. Using QTM terminology it would be when there is a net increase of M or V that increases MxV as monetary demand.

From the supply side of the economy none of the costs of production, wages, energy prices, oil, food etc can increase the quantity of monetary units used in the same number of transactions unless they increase permanently the velocity of circulation of that money and it would be necessary for this velocity to continue increasing to support continuing inflation. A second possibility is that the number of transactions contracts and there are less transactions recorded from the inflation basket using the same quantity of money which would in turn raise the average level of prices of less transactions. There is no evidence that either of these exceptional circumstances has occurred over the last 100 years meaning that all recorded inflations come from the demand side of the economy not the supply side.

When we look at the demand side of the economy we identify two theoretical possibilities to grow monetary demand. One is an increase in the stock of money and the other is an increase in the velocity of circulation of any given stock of money. In reality the velocity of circulation of money has remained fairly stable over the short term and even fallen over the longer term.

Logic has taken us to the cause of inflation as monetary demand growing faster than output and monetary demand growing as the result of an increase in the stock of money.

What causes monetary demand to grow?

From what we have said so far we must look at what causes the stock of money to grow. The stock of money has two components which are currency (notes, coins and reserves that are convertible into notes) and bank credit created by private banks from current outstanding bank loans. In the UK and US currency is less than 10% of money and 90+% has been created by private bank lending. In both countries the Central Bank has taken responsibility for managing the quantity of money. In the past this was relatively easy as in the case of the Bank of England who set ratios for private banks to follow between the amount of cash/reserves they held as a proportion of their total assets/liabilities. In the 1980`s the Bank of England had removed cash and liquidity ratios and agreed to manage the quantity of money using interest rate manipulation as seen now by adjustments to the Bank Rate. Despite the fact that it is now more difficult to manage the quantity of money the Bank of England through its Monetary Policy Committee still accepts an inflation target of 2% +/- 1% as its main goal. Arguably it would not do this if it thought that costs of production, which were totally outside its control, were the cause of inflation.

Misinformation regarding inflation

We have shown that cost push inflation is a myth yet almost 100% of articles written about causes of the current inflation highlight and focus on costs of production and what they describe as supply side shocks such as the Ukraine/Russia war with particular reference to its effect on shortages of supply and prices. Another interesting point is that many of these articles are from authors linked to the Bank of England, Federal Reserve or European Central Bank as if they are trying to deflect attention away from the role of money in this process by focusing on costs and the supply side of the economy. To understand how all these articles can persuade intelligent people that cost push inflation exists and at the same time make no reference to the Central Bank`s role in managing inflation we need to return to the period of time after Keynes death when Keynesian economists were beginning to establish themselves in the corridors of power. At that time very little attention was given to money in Keynesian models and monetary policy was just there to accommodate the fiscal actions of government. The government through the Treasury manipulated aggregate demand and the Central Bank accommodated these policies with looser or tighter monetary policies. However once cost push inflation was recognised as the main or only cause of inflation the Keynesian economists at the Treasury seemed to always be arguing for bigger and smaller deficits to boost the economy through to their chosen full employment target. Over the last 80 years of manipulated budgets there have been less than 10 surpluses and 70+ deficits. It has been suggested that deficits are what politicians want to hear, but if Keynes “General Theory” was read through carefully you would actually expect a roughly equally number of deficits and surpluses and some balanced budgets. At this point another interesting reminder from Keynes.

“We have the experience of many countries to demonstrate that unbalanced budgets are the initial cause of collapse”

This led to a line of reasoning which has currently been inherited by Modern Monetary Theory when it describes hyperinflations around the world and over time. It claims that there are a variety of causes of hyperinflation by country. This must be wrong if there is only one monetary cause of inflation which is an expansion of monetary demand faster than the rate of change of output. MMT make the mistake of confusing the cause of inflations with the cause of money printing. The cause of money printing has varied between countries, but the cause of inflation is always the same. This mistake is easily corrected by pointing out that if any or all of these identified causes did happen and the Central Bank did not respond by printing money then there would be no inflation or hyperinflation. This would then confirm a single cause of a rise in the average level of prices.

A further reason why misinformation about inflation and its cause occurs is time lags. In his 1970 Wincott Memorial Lecture Milton Friedman (1912-2006) set out important propositions that introduce the time lag:

“There is a consistent though not precise relation between the rate of growth of money and the rate of growth of nominal income”

“Today`s income growth depends on what has been happening to money in the past. What happens to money today affects what is going to happen to income in the future”

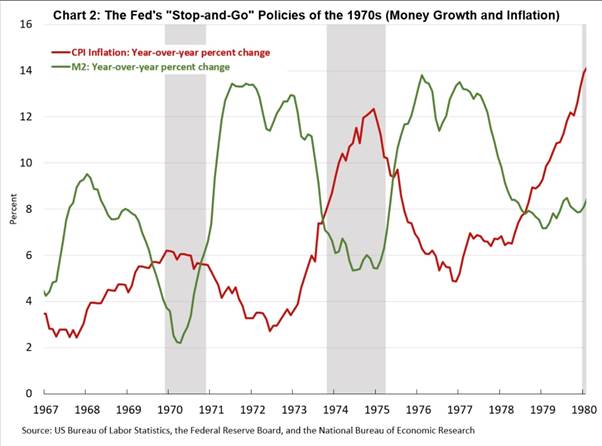

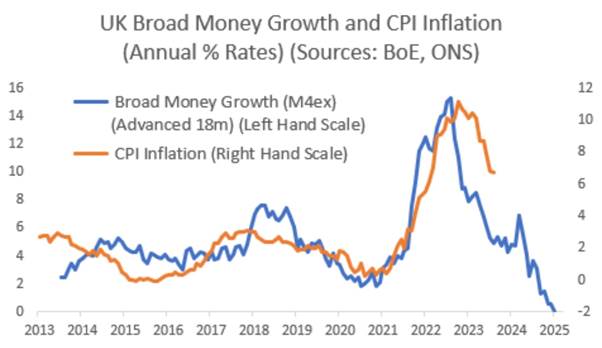

If we saw a diagram like this with the money supply increasing while inflation is falling and inflation falling while the money supply is increasing then we might be easily persuaded that there is no correlation between the growth in money and inflation giving support to those who criticise the monetary cause of inflation.

However, if one looks at money growth and adds a time lag of 18months then a relationship begins to emerge and a diagram like that below shows support for a much stronger correlation.

Let us now look for an explanation of this lagged relationship. If an economy is stable with low and steady inflation and there is a sudden boost to the money supply and monetary demand then the immediate impact on firms is for them to interpret a shift in demand from other firms product to them. The response will be to run down stocks, make plans to ramp up production and employ more productive factors. At this stage the firm has no idea that the boost is hitting all firms at the same time. Often an early effect across the whole economy is that more imports are sucked in and some potential exports are redirected into the home market. This brings about the first notable economic event on international trade which is a worsening of the current account of the balance of payments. In turn this is likely to put pressure on the foreign exchange rate of the domestic currency. A depreciation of the currency raises the price of imports and the fact that there are now more firms competing for resources raises their price and mistakenly helps to support the cost push inflation myth. Eventually firms are forced to raise their price and inflation is then recorded a year or more after the initial increase in monetary demand. 12 to 18 months is thought to be the normal time lag if as Friedman said the inflation is unanticipated. However, if firms come to think that inflation will continue and producers and consumers start to anticipate inflation then the reactions are quicker and the time lags come down. Often firms will just respond by raising price and are then accused of profiteering and this is then used as another example of cost push inflation. If the process continues towards hyperinflation then the time lag between an increase in the money supply and inflation shortens considerably and may only be days away rather than months or years.

That term deflation

Before we reach a conclusion we need to tidy up the use of the word deflation. Deflation is now most commonly used as the opposite of inflation, namely a fall in the average level of prices. However, in the past it has also been taken to mean the opposite of reflation which can create another logical problem. Reflation is an expansion in aggregate monetary demand that leads to a rise in nominal national income. This rise in nominal national income could be all inflation or there could be no inflation if an expansion in real output absorbs all of the monetary expansion. Reflation can then lead to inflation, no inflation or some inflation and some increase in real output. At this point if we introduce cost push inflation and a Keynesian analysis that states at less than full employment there is deficient aggregate demand then we can have cost push inflation which results in deflation and inflation occurring together. To accept the current convention that inflation is the opposite of deflation and avoid the problem of inflation occurring alongside deflation we need a new word to be the opposite of reflation.

Any thoughts?

Conclusion

It is not possible to have inflation in a barter economy as every rise in the price of one product will be equally matched by a fall in the price of the product it is measured against. Initially one apple buys two oranges and then one apple buys four oranges. The opportunity cost to consumers of apples has risen as oranges has fallen by an equal and opposite amount.

As Friedman said

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output”

Inflation can only be measured as more units of money used in the same number of transactions. No rise in any costs of production can result in an increase in the quantity of these units of money. The quantity of currency and reserves in the economy is directly the responsibility of the Central Bank while the amount of credit money in the economy is determined by private commercial banks which are in turn managed by the Central Bank.

We can conclude that cost push inflation is a myth and all inflations over the last 100 years and more have been caused by Central Banks and that the “buck stops” with them. This means that every single announcement about inflation and its causes should only explain why and how the Central Bank has allowed monetary demand to grow faster than the rate of growth of output.

References.

Friedman, M. (1970) The Counter Revolution in Monetary Theory. First Wincott Memorial Lecture. Occasional Paper 33. IEA

Keynes, J. M. (1923) A Tract on Monetary Reform

Keynes, J.M. (1936) The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money